The Story Behind the Beers

1870 Victorian IPA - 7.6%

IPA was the drink of the British expatriate experience. The huge success of the first London IPA in 1754 made it a staple in India. The first Burton IPA from 1823 improved on the original and boosted its popularity further. By the 1870s IPA was being served all over the UK. It was British pride in a glass. A single brewery was producing over 1,000,000 barrels of their IPA each year (about 115 million litres). It was an expensive beer to make, requiring a lot of grain and hops, making it a prestigious tipple served in upscale clubs (as opposed to working-class pubs).

The original IPAs were hopped with 100% Goldings hops, mostly from East Kent. But by the 1870s another variety, Strisselspalt, was being used along with Goldings. Our 1870 IPA is a replica of a domestic IPA, one that never made the four month long trip to India. The heat on that journey activated a then-unknown wild yeast, almost certainly Brettanomyces claussenii, givin the export IPAs a funky, stock ale flavour. 1870 is the clean domestic version since the Brett would not have had a chance to re-ferment the beer in the short time window and colder weather of the UK it faced before making it to the taps.

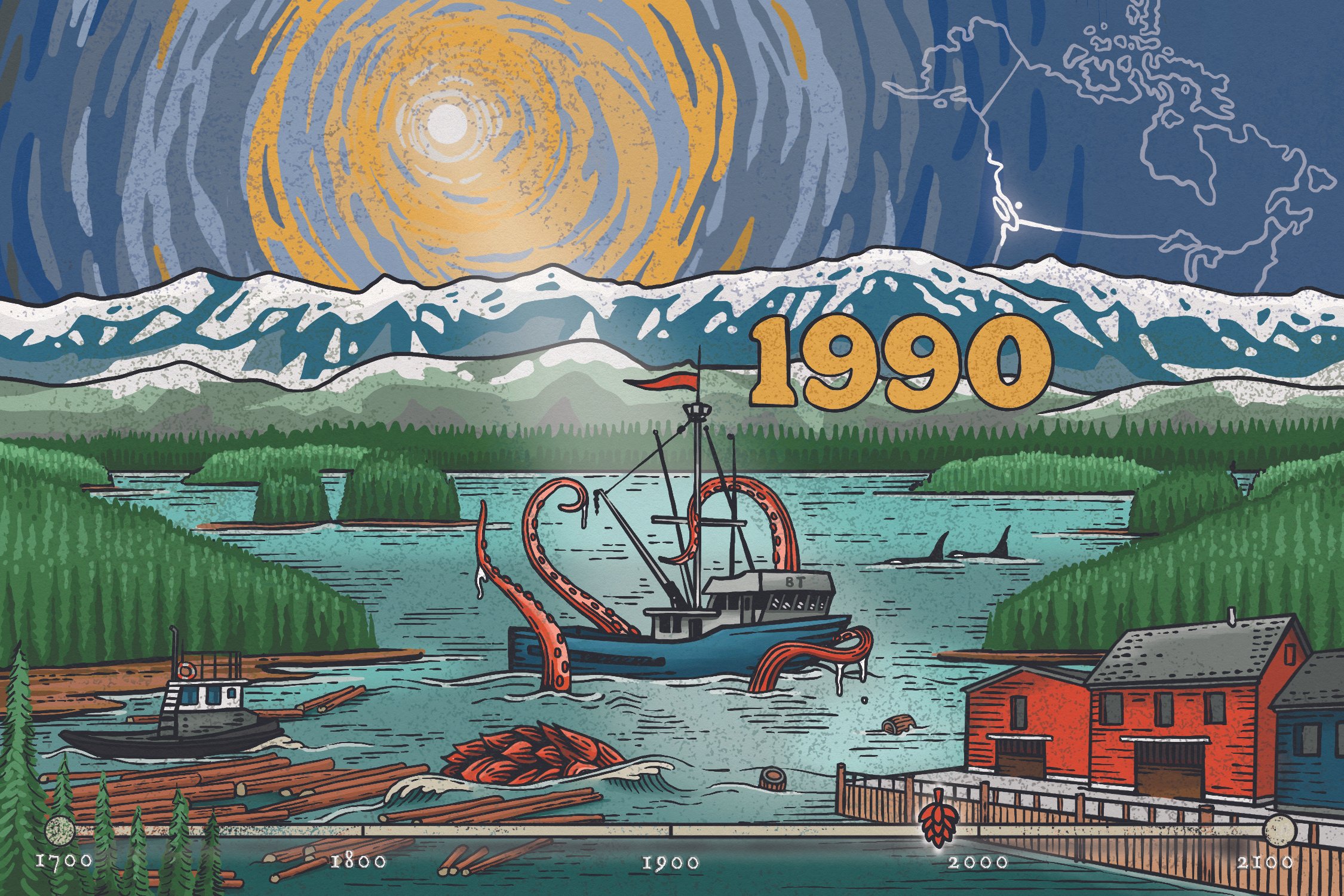

1990 West Coast IPA - 6.5%

Most beer was what we would today call craft until after the second World War. That’s when a wave of consolidation swept over the brewing industry as large companies bought small brew-pubs that were disrupted by the war. New, better transportation networks in Europe and North America combined with the Age of Advertising to launch an era of mass-produced beer. The expensive-to-make IPA nearly disappeared.

IPA came roaring back as craft beer emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, challenging decades of dominance by commodity light lagers. Small breweries on the west coast of North America started making IPA again but these new ales were different from those of the Victorian era. They used new hop varieties with big, bitter, pine and citrus flavours. These hops were originally bred for disease resistance but the breeding programs began to select for bitterness and aroma as the the popularity of IPA took off.

1990 is a re-creation of the kinds of IPA that emerged in the earliest craft breweries. It’s made with cascade, centennial and chinook hops, 2-row pale malt and crystal malts.

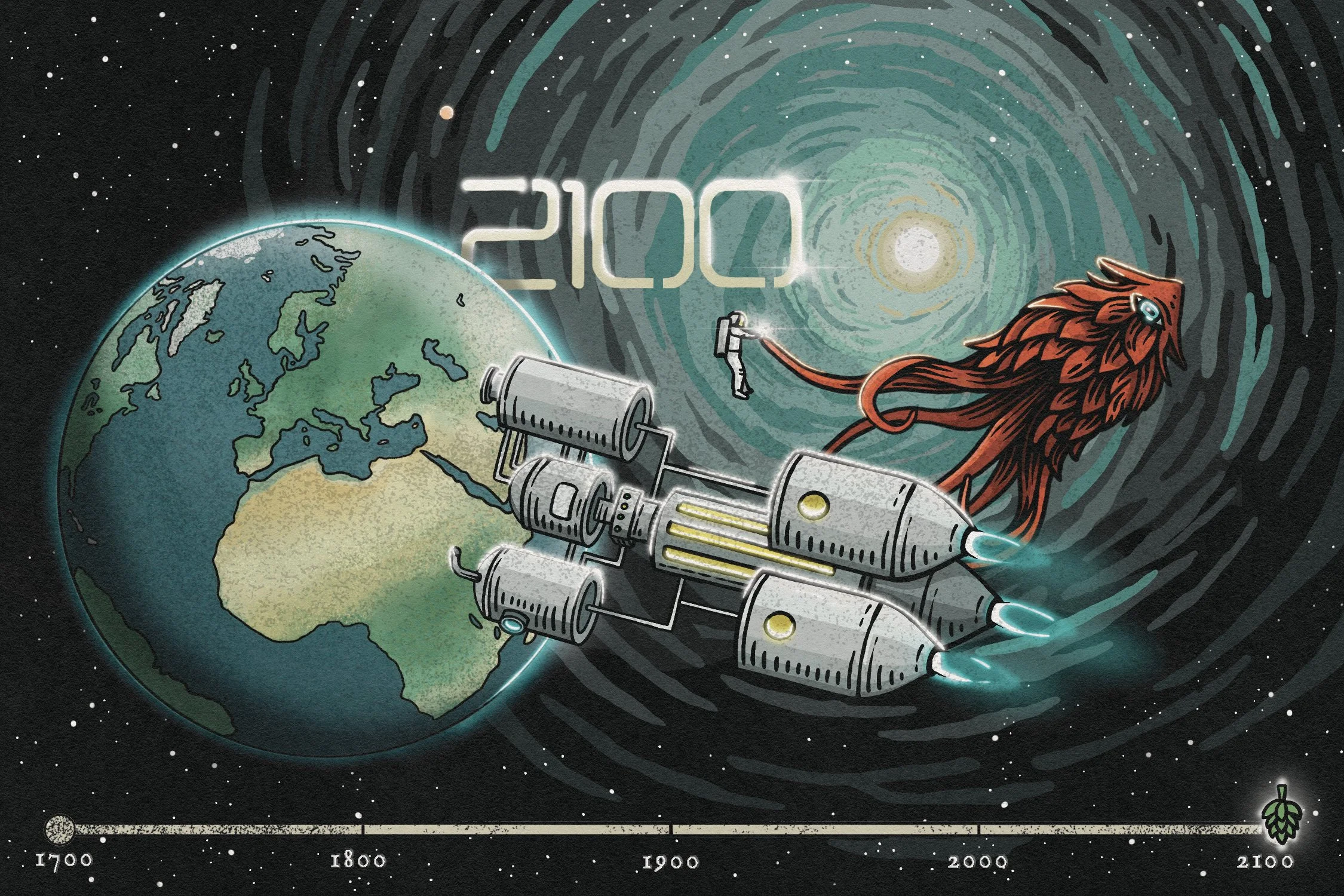

2100 Futurist IPA - 6.5%

By the early 19th century, London porter faced a crisis—not of flavour, but of arithmetic. The newly invented hydrometer revealed what no brewer had measured before: pale malt yielded far more fermentable sugar per shilling than the traditional brown malts that defined porter. Profit and efficiency drove breweries toward paler grists, but pale malt alone couldn’t produce the dark, robust character drinkers expected.

To bridge the gap, some brewers turned to burnt sugar and other “improvers,” mimicking the old flavour and appearance. Public suspicion soared, and porter—London’s proudest beer—fell under accusations of adulteration. To restore trust, Parliament passed the 1816 Malt Act, limiting brewers to malt and hops alone. But that left a dilemma: how to make true porter without the inefficiency of brown malt or the banned colourants?

In 1817, Daniel Wheeler solved it. His patented roasting method transformed pale malt into a deeply kilned black malt while preserving its extract potential. With “Patent Malt,” brewers could keep the efficiency unlocked by the hydrometer and regain the depth and honesty porter had lost.

This 1817 Porter honours that turning point—built on pale malt, sharpened with early patent malt, and shaped by the moment when science, regulation, and invention remade Britain’s most iconic dark beer.

What might the future of IPA look like? That’s what we’re exploring here. Each batch is made with experimental hops varieties and, sometimes, experimental yeasts, too. We change the malt bill as well so that each batch is different. We don’t know what it’ll taste like until it’s done, but maybe one of the batches will catch on. Who knows? Try one and let us know what you think.

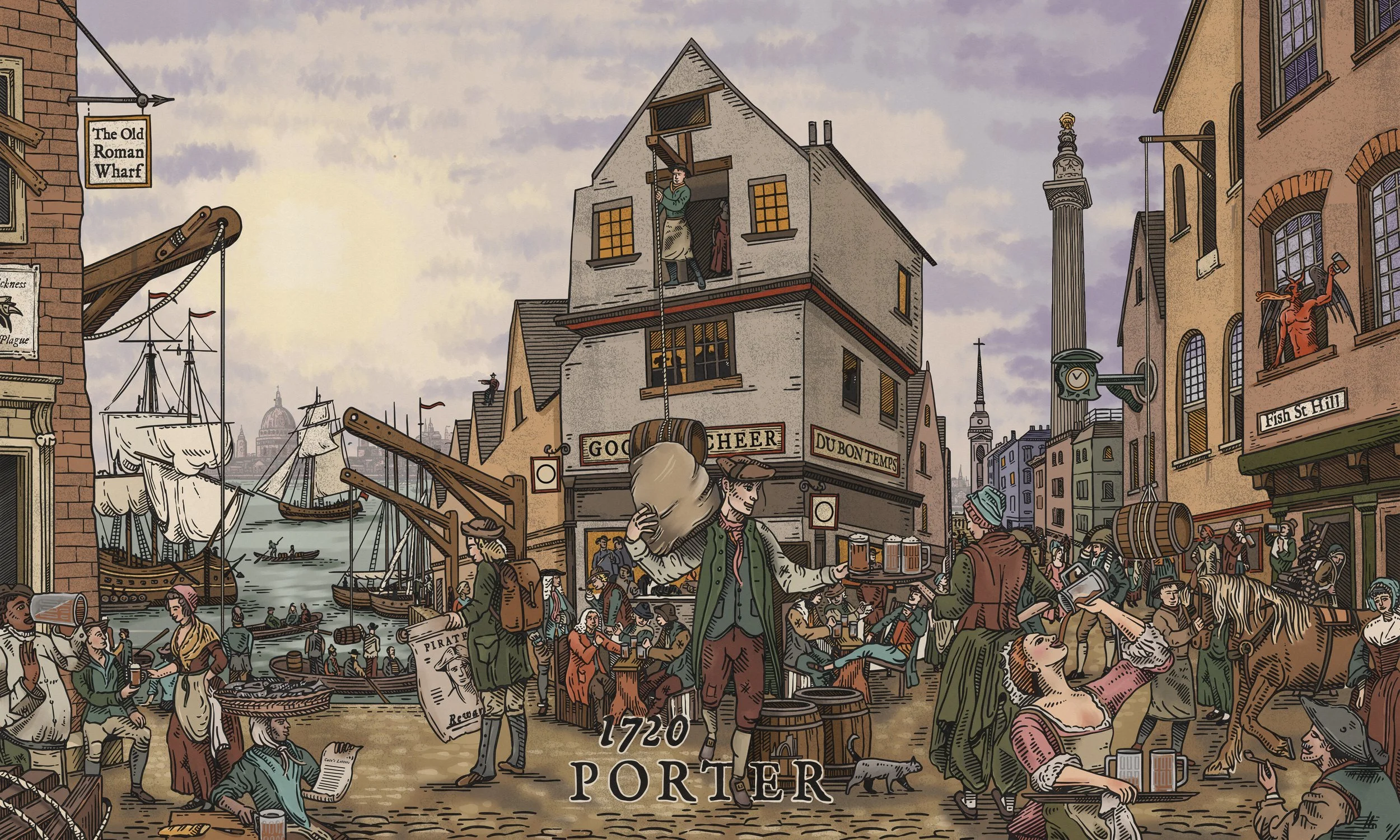

1720 London Entire - 5.7%

1817 Patent Porter - 4.5%

This is the original London porter. It’s brewed with 100% brown malt and blended with a beer containing Brettanomyces claussenii. This wild yeast, known as brett c., was in most beers produced in the British Isles before microbes were discovered and controlled for. It was slow to develop but over time it made beers drier and gave them what people called a stock ale flavour. That is, a bit fruity, earthy and funky all at once.

People enjoyed some brett c. in their porters but not too much. So, publicans would blend old and young porters in-house to get the balance of flavour their customers enjoyed. It wasn’t long before the big porter breweries started doing this in-house and then shipping the beer “entire,” that is, already blended. This saved publicans a lot of time and made porter more consistent.

This porter, being mostly made of brown malt, is, well, brown. It’s not like the porters of today, but is their ancestor. It’s named after the London porters who used this beer for energy as their unloaded ships and delivered cargo by hand around the City.

For homebrewers interested in replicating this, you can’t. Sadly, modern brown malt does not have any of the enzymes required to convert starch to sugar and a custom malt is required to make this beer. A 100% brown malt beer using modern malts would be nothing but unfermentable starch.

1901 Export Porter - 4.7%

This hoppy porter is a re-creation of one of the lighter beers to be exported to the Caribbean at the end of the Victorian era. The export porter tradition began in the late 1700s as big, sometimes over 10% alc/vol beers were exported to the Baltic states. Strong porters were also sent to India, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean but, as with many beers in the period around the year 1900, they became much lighter as the temperance movement, changing tastes, and competition with lighter German lagers drove down the strength of British ales.

1959 Irish Stout - 3.8%

This rich, roasty and chocolaty stout is served on a nitro tap and is a full-flavoured drink for only 3.8% alc/vol. It is a representation of a style that was refined in the mid-20th century into some world-famous versions that are today known around the world. This beer is a representation of a regional brewing tradition of tasty, low-gravity beers that started being served on nitro taps in the late 1950s..

Råøl (Raw Ale)

Dating back to the age of the Vikings, Råøl (or kornøl) is an un-boiled farmhouse ale brewed with juniper branches and berries. Its character comes from a remarkable yeast—fiery, fragrant, and fast-working—that ferments at nearly twice the temperature of conventional strains. The result is a burst of bright fruit esters woven together with the resinous aromatics of juniper.

Råøl is served nearly flat and remains naturally hazy, just as it would have been in longhouses and farmsteads centuries ago. The proteins stay suspended, giving the beer its soft, rustic appearance.

For generations this style survived quietly in remote Norwegian farmhouses, passed down through memory rather than written recipes. Then, in the early 2000s, curious brewers and historians visiting communities like Hornindal and Voss documented these living traditions—juniper-infused mash water, wooden vessels, and the treasured kveik yeast strains dried on rings above the hearth. The global brewing world was astonished: an unbroken line of Viking-era brewing had endured, hidden in plain sight.

This beer stands in that lineage—a modern expression of a style nearly lost, revived through its remarkable rediscovery and the dedication of the farmhouse brewers who kept it alive.

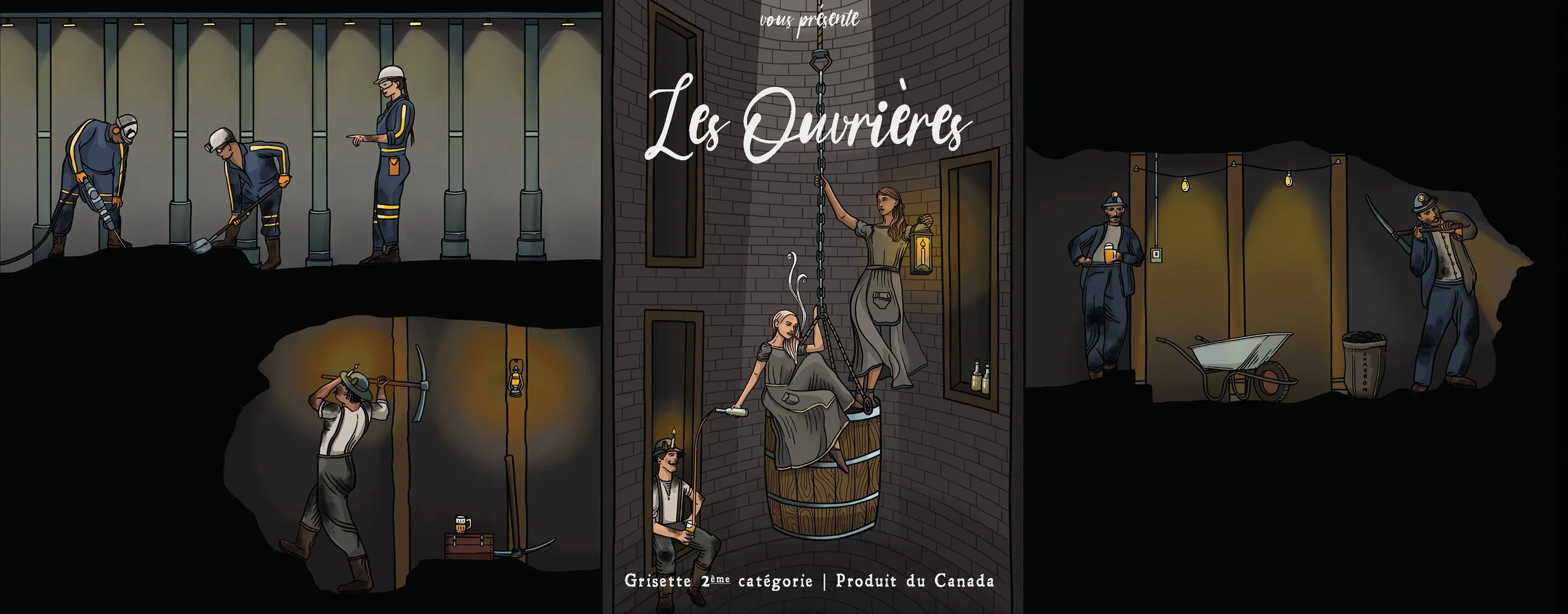

Les Ouvrieres (Grisette) - 3.2%

Born in the coal and limestone mining regions of Belgium’s Hainaut province, Grisette was the light, refreshing ale brewed for workers who spent long days underground. Its name comes from the grisettes—young women in simple grey dresses—who carried trays of these small, bright beers to miners as they emerged from the shafts, dusted in the same grey stone. The beer and the women became inseparable symbols of relief, hospitality, and everyday resilience.

Grisette is a modest ale: low in alcohol, naturally hazy, and built to quench thirst rather than amaze with strength. Wheat in the grist gives it a soft, clouded body, while notes of fruit and spice hints at the farmhouse roots shared with saison. Served young and lively, it was meant to be restorative—a cool breath of air after hours in the dark.

Though nearly forgotten in the 20th century, the style has recently been rediscovered by brewers drawn to its simplicity and its story. Grisette is a reminder that beer’s history is in the daily rituals of workers whether the clatter of tools on stone, or the clink of glassware behind a bar.

This modern Grisette honours that heritage: light, joyful, and tied to the lives of ordinary people who helped shape brewing history.

This beer begins with a medieval tradition: gruit, the unhopped herbal ales that dominated European brewing before hops became common. Bog myrtle—one of the classic gruit herbs—provides the aromatic backbone. But this beer also tells a story from 14th-century Liège, where the shift toward hopped beer first took shape.

In 1337, Liège received a new prince-bishop whose appointment angered many locals. In an attempt to win support, he granted the city an exclusive privilege over the textile trade. While this benefited urban merchants, it devastated the surrounding countryside, which depended on textile production for income. Rural households suddenly struggled to afford grain and, more critically, the grain taxes tied to brewing—an essential part of everyday sustenance.

Around this time, monastic communities—including those associated with the great Abbey of St. Bertin in nearby Flanders—were among the first in the region to cultivate hops. Though much of their hop harvest went toward rope and other practical uses, they also preserved knowledge from earlier texts (such as the 11th-century writings of Abbot Adelard of Corbie) describing hops’ remarkable ability to keep beer stable for longer periods. Crucially, hopped beer could be brewed with slightly less malt while still lasting longer—an enormous advantage for people facing high grain costs.

This beer imagines what those first transitional brews might have tasted like: a lightly hopped gruit, still herbal with bog myrtle, but touched with the preservative bitterness monks were just beginning to refine. It pays tribute both to the resilience of medieval brewers and to the monastic communities whose quiet innovations nudged Europe from the age of gruit into the age of hopped beer.

St. Bertin Beer - 3.8%

1890 Pattersbier - 3.5%

Patersbier—literally “Father’s Beer”—was the quiet, everyday ale brewed in Belgian abbeys for the monks themselves. Unlike the powerful Tripels and Dubbel-style beers they produced for sale, Patersbier was light, modest, and nourishing: a table beer meant to accompany work, prayer, and study. By the late 19th century, around 1890, many monasteries were refining this humble beer into a delicate, pale ale brewed from the same grist as their stronger beers but run off as a weaker second wort. It was simple by design—clean, bright, and sustaining.

This 1890 interpretation captures that era of monastic brewing as it stood on the threshold of modernity. Pale malt had become more widely available thanks to improved kilning technologies, and continental hops were prized for their subtle spice and herbal aroma. Fermentation temperatures were carefully controlled in cool stone-walled breweries, producing an ale that was crisp, lightly fruity, and effortlessly drinkable. Patersbier was never meant to impress visitors; it was brewed for the refectory, not the public house—beer as daily bread.

Nearly forgotten outside the cloister walls, Patersbier has found new life among brewers who admire its restraint and its role in monastic life. This version honours that tradition: pale, refreshing, gently hopped, and rooted in the quiet rhythms of the abbey. A small beer with a large history, it offers a glimpse into what monks themselves drank when no one was watching—an honest expression of the brewer’s craft at its most humble and sincere.